Ontario Plants

Foraging Gardens

Foraging gardens are designed to be low-maintenance, highly productive food gardens that produce things to eat all year round. They may look natural, but they definitely need to be planned.

You don’t have to know everything to begin with. You learn what you can, and put in the work – and go from there. You can learn as you go. This is a good exploration of a forest garden, for example.

Intensive Gardening

We like to help design intensive, packed gardens with lots of life. There’s no reason to have bare soil, and many, if not most, plants expect to have competition. For forests and wild spaces, we prefer packed hedges and dense foliage, where plants live close together.

The following is a good introduction to one highly developed method of intensive gardening – a Miyawaki Forest, named after a Japanese scientist who dedicated his life to reforestation projects. The idea is to create thriving, densely packed native vegetation quickly and with a minimum of labour.

What Does "Native Plant" mean?

What do we mean when we say “Native plant”? There are serious problems with whatever definition we use. When they use the word “Native”, most purists mean “any plant that was here before European contact”. The problem is that this is a biologically, environmentally and historically nonsensical concept. Some notion of “native” can be very useful for our current environment, but purists seem bent on freezing an image of Ontario in place, as if in amber. In fact, Ontario’s climate, flora and fauna have varied so wildly over time, it’s difficult to know even what to say about it. There’s no historical stability, especially in recent historical terms. 12,000 years ago, the plant life in Ontario was close to “zero”. It’s been dozens of things since then.

What do we mean when we say “Native plant”? There are serious problems with whatever definition we use. When they use the word “Native”, most purists mean “any plant that was here before European contact”. The problem is that this is a biologically, environmentally and historically nonsensical concept. Some notion of “native” can be very useful for our current environment, but purists seem bent on freezing an image of Ontario in place, as if in amber. In fact, Ontario’s climate, flora and fauna have varied so wildly over time, it’s difficult to know even what to say about it. There’s no historical stability, especially in recent historical terms. 12,000 years ago, the plant life in Ontario was close to “zero”. It’s been dozens of things since then.

A Common Northern Heritage

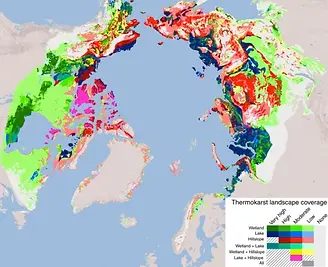

All northern floral ecologies tend to be weirdly similar, especially when compared to tropical ones. Different tropical rainforests tend to be quite unique. Also, continents like South America and Africa can have radically different biomes, despite the similar climates. As for origins, there’s no northern equivalent of a “Gondwanan” ecological distribution as in the south. Gondwana is our name for an ancient continent that included Antarctica, India, Africa, Australia, etc., and the animals and plants there can be similar to each other. Plants in a place like Australia often have a weird similarity to those in South America, so we talk of “Gondwanan distributions”. But in the North, generally, from Yukon to Saskatchewan to Scotland and Siberia, there tends to be a more uniform sameness about the animal and plant life. One picture of a northern ecology looks much like any other.

There are lots of reasons for this.

Scraped Away by the Ice

At least a dozen times in the past few hundred thousand years, ice sheets have totally transformed the landscape and scraped everything away from Ontario, dumping it in the south, from soil to huge rocks to, well, everything. Imagine a great big frozen eraser obliterating everything in its path. We are currently in an “interglacial” period right now, part of the extended “Holocene” interglacial period. Each time the glaciers come and go, when plants rebound after glaciers retreat, the plants that creep back north might be different from the last time around. The previous really serious interglacial was 115,000 years ago, when it was much hotter than today and the sea level was significantly higher, and huge amounts of land around the world were under water. But between then and now there have been countless “mini interglacials”, each one involving advancing and retreating glaciers. During each warm period, the local flora and fauna would have been at least slightly different, and in some cases very radically different.

For example, the last short warm period saw vast numbers of trees and plants in Ontario that are no longer here. Osage Orange, for example, was found across eastern North America, some of them pretty far north. It produces fruit that’s both bizarre and eaten by nothing now alive. Today, though, the osage orange has, in historical memory, been restricted to an incredibly tiny range in Texas-Oklahoma. It appears that before this warm period, the tree’s seed disperser went extinct, making it an “evolutionary anachronism”, a leftover. When the glaciers retreated, there was no longer any animal to re-spread its seeds for re-colonization, and it remained trapped in its tiny refuge in Texas. But today, it survives very well in Ontario, and is a magnificent tree. This is not the only tree for which this is true, or shrub or plant. There are many of these plants, all over the world, that seem to be partly “lost”. Some pines are only found in Mexico or the American South-West, but they once grew all over Ontario. Why aren’t they there now? It’s possible the climate is different, but it’s also possible that they’ re not in Ontario only because of historical accidents or contingency. They just didn’t make it back after the ice, for no reason that has any modern implications. If they were once here, and now are planted here and do well, then do they belong here or not? Some say sure, others say no. It’s possible to argue both positions. What if the only surviving member of a group of plants once common in Ontario is now found in Europe? Can we say that it, or something much like it, belongs here? For every argument we make one way, we can make one the other way.

Constant Climate Change

The climate of Ontario has fluctuated wildly. The most extreme has been due to glaciation, but even during long periods of glacial stability, the climate has varied so much that plants have advanced and retreated. Most recently, there has been a long but relentless Holocene (our period) decline in hemlocks, for example. Soils have changed, too.

The whole plant biomes could move up to 20 km in a century, or even more, even during an interglacial period. This could be quite chaotic. The upshot of this is that “native” means something only in the sense that plants move in and move out and emerge and die out with astonishing speed, and they’re broadly North American or Circumpolar. But predicting what they’ll be in the next chaotic climate change period, all of which is natural, is impossible. So much depends on contingency and chance.

Circumpolar Distribution

One major issue is the distribution of many plants. While there are many local varieties, they often breed with those from other northern climes, like European varieties, or Siberian and Asian varieties. This is because many of these genera and species have strong, recent and repeated links to others across the northern hemisphere. Part of the reason are those glaciers, again – chasing the plants south, and then retreating to allow plants to slowly creep back north. This meant that new local varieties were constantly evolving. But many of these plants are equally good at living in other northern climes, and serve the same ecological purposes in any northern country. And then there are animals. For many plants, their circumpolar distribution is explained by either a common origin or, more often, being spread by animals across the polar regions. Animals living in boreal regions travel a lot, and seeds can end up moving between Eurasia and North America pretty easily. This has likely always happened, and it may explain why there’s basically fluid gene exchange between many northern plants. It can also explain why species or varieties seem to emerge and disappear so readily. Sometimes, they just cross, and then the crosses replace one or all of the original varieties.

How deep do we go?

One tree with a claim on being native is the freaky, prehistoric-looking Ginkgo tree. Globally ubiquitous for 200,000,000+ years, its fossils are found around the world, even in Antarctica. And then, … they diminished and faded into history. By a few hundred years ago it was isolated to one tiny region of China. This was the last stand of the ginkgo, the last refugia, until humans started transporting it. It’s likely that several things worked against them, but they seem to be “out of phase with their dispersal agents”, as in they have none. Whatever dispersed their seeds went extinct. It’s thought the dispersal animals were dinosaurs. With no more dinosaurs around, how can their seeds travel? In a strict, purist sense, the Ginkgo tree is not native to Ontario. But in a larger sense, this tree should be native to virtually everywhere, including Ontario. It grows in Ontario fine. It likes it. It’s perfectly at home.

A Human Landscape: Not an Untouched Idyll

When we say native, do we mean just “Ontario from 2000 years ago to AD 1600”? What do we even mean by that? This is the definition usually taken by purists, who argue for an essentially racist definition of the term often without even realizing it.

The truth that’s hard for modern Canadians to incorporate into their worldviews is that Ontario and the rest of Canada wasn’t some unspoiled wild arcadia before Europeans got here. That’s a weirdly culturalist, basically racist way of seeing history, as if native nations were just savages hunting animals in the woods.

There was agriculture everywhere, and even where it wasn’t farmed, cropped or maintained, the landscape was deeply manicured. It was nothing like “natural”. It was a consummately human ecology.

There were few peoples as successful at agriculture as the native peoples of Southern Ontario, descendants of the Eastern Woodlands cultures. They have names like the Haudenosaunee (the Six Nations), among many other nations, and they were among the world’s most prolific agricultural peoples.

Even where there weren’t cornfields, whereas Europeans saw an untouched wilderness, what was really there were orchards, managed forests, open areas designed to attract game and keep soils fertile, and carefully cultivated landscapes. Lots of the plants that Europeans thought were just there by chance were brought where they were by people using the entire landscape as their collective gardens, tending them and removing things they didn’t like or need.

This “natural” spread was managed or altered by humans long before Europeans arrived.

Southern Ontario was a deeply human-managed landscape, without any concern for what was “native” or not, way before Europeans got here. Many plants would have been brought by First Nations to various places, tended, cared for, spread, moved between regions and zones. Wild rice would be encouraged, native reeds would be removed or cut away. Berry bushes would be planted in convenient locations.

Authentic Authenticity

What flora and fauna are the “authentic” Ontario? Why are we privileging the immediate “now” over any other time in the past? How do we pick just one of those past times? Why not a different interglacial period, or why not the landscape as it was 175 or 200 million years ago? Why not 75,000 years ago? Why don’t we love the tundra-plains of 9,000 years ago? Why not plant hemlocks everywhere and undo the relentless retreat of hemlock forests?

Purists are up against a serious problem: There are many historical Ontarios, and in fact it presents nothing remotely like stability. The environment has changed so much, so radically, so often and so consistently that anything we say about it at any period isn’t true of it very shortly after. The truth is that Ontario is a landscape in a state of constant, relentless, endless change. New species arise, disappear, migrate away, are introduced, evolve, replace others. There are broad patterns, but nothing that anyone would be able to just put a finger on and say, “We will freeze everything here as is was at this precise moment and say this is what it always must be”. We can’t create a frozen landscape, locked in time, sealed in a historical box as an eternal platonic object.

What’s Native? What’s Invasive?

As hard as it is to define “native”, it’s just as hard to determine what we mean by “invasive”. In general, it’s meant to describe a plant that isn’t native, and that also crowds our (even endangering) native plants. An invasive plant can turn a field with hundreds of diverse plants into a monocrop of one dominant species. Gardeners “know” an invasive when they see one. But not all of these are alien invaders. Some are native, too.

But for the definition of native, we need to avoid turning the idea of “native” into a weird, culty religion. It has to make biological sense.

On blogs and in forums, gardeners often argue with zealous intensity, shaming each other, creating “tribes” or factions of belief, accusing each other of impieties or transgressions against ever stricter orthodoxies. The idea of “native” becomes very much like a faith-based dogma, not related to reality in any meaningful sense.

But life doesn’t play by the rules of dogma in this way. Life doesn’t care about our concepts of rightness and wrongness. Even the definition of life is a problem. What, exactly, is alive? Because it’s so hard to define, we don’t have an absolute “definition”, but speak rather of “characteristics”. Things that we think of as alive have some, most or all of these characteristics.

Biologically, a definition of “native” has to be less dogmatic and more like the definition of “life”. If we abandon arbitrary, strict definitions and absolutes, giving up the ahistorical “cult of the now”, we can define broad characteristics of what constitutes “native”. These characteristics can be summarized, and can be used to guide what we plant.

Broadly localist or North American: Always keep in mind whether something has a history in the region, in neighbouring regions, or more broadly could or should belong here.

Does it have a circumpolar distribution? Does it extent up from southern climes?

Could it occur naturally?

Is it a different kind of thing that already lives in Ontario?

Does it behave in the same way as other Ontario plants?

Does it relate to Ontario or Ontario plants in come consistent or justifiable?

Maintaining varieties: Varieties and species appear and disappear all the time. But we don’t need to submit to the extirpation of one variety by another.Cormorant Garamond is a classic font with a modern twist. It's easy to read on screens of every shape and size, and perfect for long blocks of text.

Instead, we can try to maintain a local variety by choosing not to plant an imported one. This could be a newly emergent variety, as well as a historical one. There’s nothing inherently wrong with “new”. With shrubs, for example, we could plant local dogwoods and not bring in other dogwoods that might replace them over time, or we could plant a new version of a local dogwood over an imported one. We can choose to seek out unique local varieties and keep them going.

Role: Does a plant have an clearly identifiable role that we can assist?

Does it interact well with other local flora and fauna?

Do insects like it? Which insects? What else do those insects do?

This would apply equally to native plants.

Natural Balance: Does the plant massively imbalance what’s going on in the landscape?

Does it add to the environment?

Does it help bring biodiversity and ecological growth and development?

Invasiveness: Some plants, when introduced, cause massive change that acts like serious damage to the environment. Also, gardeners are usually seeking to exclude rapidly spreading plants that choke out others.

Change is always happening, but some change can be hugely consequential for local wildlife.

A single species can crowd out or destroy the habitat of dozens of other species. In Ontario, Hogweed and Purple Loosestrife can cause huge amounts of damage.

However, not all of these invasive, dominating species are “non-native”. There are native plants that can overrun a garden, too, choking out everything else, like goldenrod (solidago canadensis), or milkweed (asclepias syriana), or cup plant (silphium perfoliatum).

Balancing Human and Natural Needs: Sometimes, a native plant can be inconvenient or inappropriate for a human setting. People don’t need a tree here, or need something else there. They want a certain kind of food or crop, or they want a particular look in a landscape. Humans have been tending and managing Ontario’s plant life for ten thousand years. We still do it. Our needs are part of the environment; we need to live here, too. As part of our environment, in the world that we call home, what we need should have some place on the hierarchy of environmental considerations, so long as we respect the same needs of others. Practiced respectfully, and with knowledge and care, there’s no reason why human needs and the needs of nature and wildlife have to conflict. It’s a choice we make, not an inevitability. We should make good choices. Humans are part of the natural world, too.

Food: Humans move lots plants around the world. Apple trees that we farm aren’t native to North America. Neither are cultivated grapes. On the other hand, North American vegetables now dominate whole cuisines in other parts of the world. Neither chiles (for kimchi), nor potatoes, nor corn, nor squash nor, for that matter, even rice itself are native to Korea, yet people there grow them and eat them in huge quantities. Many food crops are North American in origin, from tomatoes to corn, but there now are Russian and Egyptian varieties, too. Can anyone say where Taro or Okra authentically belong? The same is true for herbs. Where do we draw the line? And what about fruiting trees, shrubs, bushes, ground cover and vines that serve human diets? The hypocrisy of native plant purism and its religious overtones is most apparent with the attitude towards food plants.

Our Operating Native Plant Principles

This is a discussion of just some of the problems with the idea of “native plants”. Strictly interpreted, the concept is almost racist, trapped in the “Tyranny of the Colonial Imagination”. In another way, it’s also a “Tyranny of the Now”, or “Now-ism”, the idea that whatever is in place at this precise moment is the natural state for all time, and that it’s not just weirdly steady-state, but that this perfected ideal is preferable and desirable. Would people have said this about the rocky, thin-soiled, ice-fringed tundra of Southern Ontario of 15,000 years ago? Should it always be tundra? These zones could move radical distances in short periods of time. What was “native” might not be “native” 100 years later. Must these things remain fixed, and never change? Should we force them to stay the same?

All of the definitional problems aside, maintaining local diversity and the unique, if evolving, local character is as much for us as it is for the environment. The landscape will just do what it does. Especially in Ontario’s case, it’s not historically static. That said, we certainly appreciate what makes our environment unique, and whether or not it changes on its own, there’s no reason to cause damage.

We follow these Basic Principles

Do as little harm as possible: never sell or grow invasive plants (regardless of origin); Don’t plant where it’s inappropriate; Don’t destroy valuable local environments to replace them (with grass, say), or gratuitously cut down trees for no good reason.

Choose native plants and species, where possible, and prefer them over non-natives.

Encourage diversity in species, so that the plants work together. Avoid monocropping.

Encourage growing from seed, for maximum genetic variation.

Plant appropriate plants together, so that they work together, using natural environments as our cue.